Carroll Quigley: The Georgetown Professor Who Saw Too Much

In the 1960s, a history professor at Georgetown University was handed something almost no one gets. Access. Real access. To the private archives of a network he had studied for twenty years.

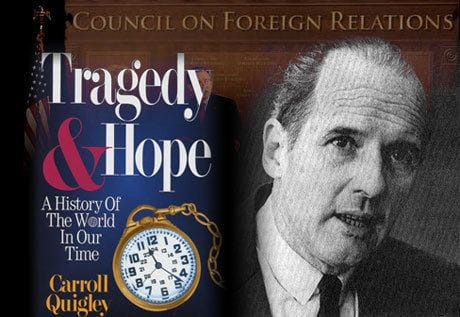

His name was Carroll Quigley. And his credentials weren’t fringe. They were as establishment as it gets.

He earned his PhD from Harvard. He taught at Princeton. He taught at Harvard. Then for thirty-five years, from 1941 to 1976, he taught at Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service, the oldest school of international affairs in the United States. A Jesuit institution, founded by Father Edmund A. Walsh, S.J., that has trained generations of American diplomats and foreign policy professionals.

Quigley wasn’t just a professor. He was a consultant to the U.S. Department of Defense. A consultant to the United States Navy. He advised the Smithsonian Institution and the House Select Committee on Astronautics and Space Exploration. Georgetown awarded him the Vicennial Medal in 1961 and the 175th Anniversary Medal of Merit in 1964. He won the Faculty Award four consecutive years before his retirement.

Alumni from 1941 to 1969 voted his course on the Development of Civilization as the most influential course in their undergraduate careers.

Bill Clinton sat in his classroom and would later cite him as a formative influence.

This wasn’t an outsider lobbing accusations. This was a man the institutions trusted enough to let inside.

The network Quigley studied operated through several affiliated organizations, chief among them the Council on Foreign Relations. Founded in 1921, the CFR has been described as possibly the most influential private organization in American foreign policy. Its membership has included senior politicians, secretaries of state, CIA directors, bankers, lawyers, professors, and prominent media figures. It publishes the journal Foreign Affairs. Its members slide into cabinet-level positions across both Republican and Democratic administrations with remarkable consistency.

According to Quigley, the CFR was the American branch of a network that included the Royal Institute of International Affairs in London, both tracing back to the Round Table Groups organized in the early 1900s. These were not separate organizations operating independently. They were, in Quigley’s words, interlocking.

As Quigley himself wrote: “I know of the operations of this network because I have studied it for twenty years and was permitted for two years, in the early 1960’s, to examine its papers and secret records.”

What Quigley found in those archives, he published in a 1,348-page book called Tragedy and Hope: A History of the World in Our Time.

His conclusion should have shaken the foundations of how we understand power:

“The powers of financial capitalism had another far-reaching aim, nothing less than to create a world system of financial control in private hands able to dominate the political system of each country and the economy of the world as a whole.”

Read that again. This wasn’t some guy in a basement connecting red strings on a corkboard. This was a Harvard-trained, Pentagon-consulting, Georgetown professor with insider access, writing from primary sources, documenting what he called systematic coordination among financial elites.

He wasn’t theorizing. He was reporting.

What He Actually Found

Quigley traced how networks of financial institutions operated through central banks, coordinated policy behind closed doors, and functioned largely outside anything resembling democratic accountability.

In Tragedy and Hope, he discussed Walter Rathenau. Rathenau ran the German General Electric Company (AEG) and held scores of corporate directorships. In 1909, Rathenau wrote something remarkable in the Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse:

“Three hundred men, all of whom know one another, guide the economic destinies of the Continent and seek their successors from their own milieu.”

This wasn’t speculation from an outsider looking in. Rathenau was heir to the AEG fortune. He sat in the rooms where these decisions happened. He knew these men because he was one of them.

In 1922, shortly after serving as German Foreign Minister, Rathenau was assassinated. Whatever else he knew died with him.

Then the Book Disappeared

Here’s where it gets interesting.

After Tragedy and Hope was published, something strange happened. The book became almost impossible to find.

In Quigley’s own words: “The original edition published by Macmillan in 1966 sold about 8,800 copies and sales were picking up in 1968 when they ‘ran out of stock,’ as they told me. But in 1974, when I went after them with a lawyer, they told me that they had destroyed the plates in 1968.”

Quigley continued: “They lied to me for six years, telling me that they would reprint when they got 2,000 orders, which could never happen because they told anyone who asked that it was out of print and would not be reprinted.”

Copies became collector’s items. Researchers who understood what Quigley had documented hunted for them. The evidence he presented, drawn from primary sources within elite institutions themselves, was never refuted.

The book just quietly vanished from shelves.

He Wasn’t Alone

Quigley’s work found echoes in other scholars willing to follow the money where academia feared to go.

Antony C. Sutton held a research fellowship at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution from 1968 to 1973. He dug through declassified archives, corporate annual reports, and shipping manifests. In books like Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution and The Best Enemy Money Can Buy, he documented how American financial interests funded multiple sides of 20th century conflicts.

Both men faced professional consequences for what they found. Neither had their documentation successfully challenged.

Modern Science Confirms the Pattern

Decades after Quigley wrote, researchers at ETH Zurich decided to map the actual ownership networks of global capitalism. In 2011, they analyzed 43,060 transnational corporations.

What they found was striking. Just 147 firms, predominantly financial institutions like Barclays, JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs, and Morgan Stanley, controlled 40% of total network wealth through recursive ownership structures.

This wasn’t conspiracy theory. It was published in the peer-reviewed journal PLoS ONE. It was math.

Whether you call it Rathenau’s 300 men, or the ETH study’s 147 firms, the pattern holds. An infinitesimally small group coordinates decisions that affect billions.

What This Means Right Now

In 2014, researchers Martin Gilens of Princeton and Benjamin Page of Northwestern published a study that should have been front page news everywhere. They analyzed 1,779 U.S. policy outcomes from 1981 to 2002.

Their finding was blunt. Average citizens’ preferences had statistically near-zero independent impact on policy. Economic elites and organized business interests got what they wanted. The rest of us got whatever overlapped with their interests.

The mechanisms Quigley documented haven’t gone away. They’ve evolved. The Council on Foreign Relations still meets. The Bilderberg Group still convenes. The Trilateral Commission still coordinates.

You don’t have to believe in shadowy conspiracies to understand this. You just have to read what a Harvard-trained, Pentagon-consulting professor at America’s oldest school of international affairs documented when he was given access to the archives. And ask yourself why that book became so hard to find.

Eric Daniel Buesing spent 22 years researching elite power structures, building on Quigley and Sutton’s foundational work. His book The Hidden Hand: Wealth, Power, and Control from Pharaohs to Corporations traces these patterns from Sumerian temple economies to modern corporate networks.

Pre-order now: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-hidden-hand-eric-daniel-buesing/1148336792