The Kompromat Cycle: First They Bribe You, Then They Blackmail You, Then You Die

Two plane crashes. Three months apart.

Jaime Roldós, president of Ecuador, died May 24, 1981 when his plane went down near the Peruvian border. Bad weather, said the official report.

Omar Torrijos, Panama’s leader, died July 31, 1981 when his plane hit a mountain in clear weather. Some accounts mention a tape recorder with a bomb. Another accident, said investigators.

Both men had refused to cooperate with American economic interests. Both were dead within 97 days of each other.

John Perkins knew why. He’d worked with both leaders, trying to trap their countries in unpayable debt. He watched from the sidelines as they died. He tried to write about it in 1982. Someone stopped him. He tried again four more times over twenty years. Each time, threats or bribes silenced him.

In 2004, Perkins finally published “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man.” It named names, detailed methods, and became a massive international bestseller despite brutal attacks from establishment critics.

The system he exposed continues today, perfected by China and deployed across three continents.

The Woman Who Taught Him the Game

Her name was Claudine Martin. At least, that’s what her business card said. Special Consultant. They met at the Boston Public Library in 1971. The meetings moved to her Beacon Street apartment.

She was attractive, brilliant, and cold. She used cocaine and wine. She used seduction. And she used his NSA personality profile (somehow she had access) to manipulate him with surgical precision.

Perkins had just returned from Peace Corps service in Ecuador. Now age 26, with no formal training in economics, he’d been hired as an economist at a Boston engineering firm. Within months he’d become chief economist.

Claudine’s job was to prepare him for the real work.

She told him exactly what that work would be: justify enormous loans for countries that couldn’t afford them. Use whatever projections necessary to make the numbers work. The loans would fund massive infrastructure projects. American corporations would get the contracts. The money would flow from Washington to the poor country and straight back to American bank accounts. The country would be left with unpayable debt.

Then the real extraction would begin. When the country couldn’t pay, the United States would own them. Their UN votes. Their military bases. Their oil and minerals. Their policies, foreign and domestic.

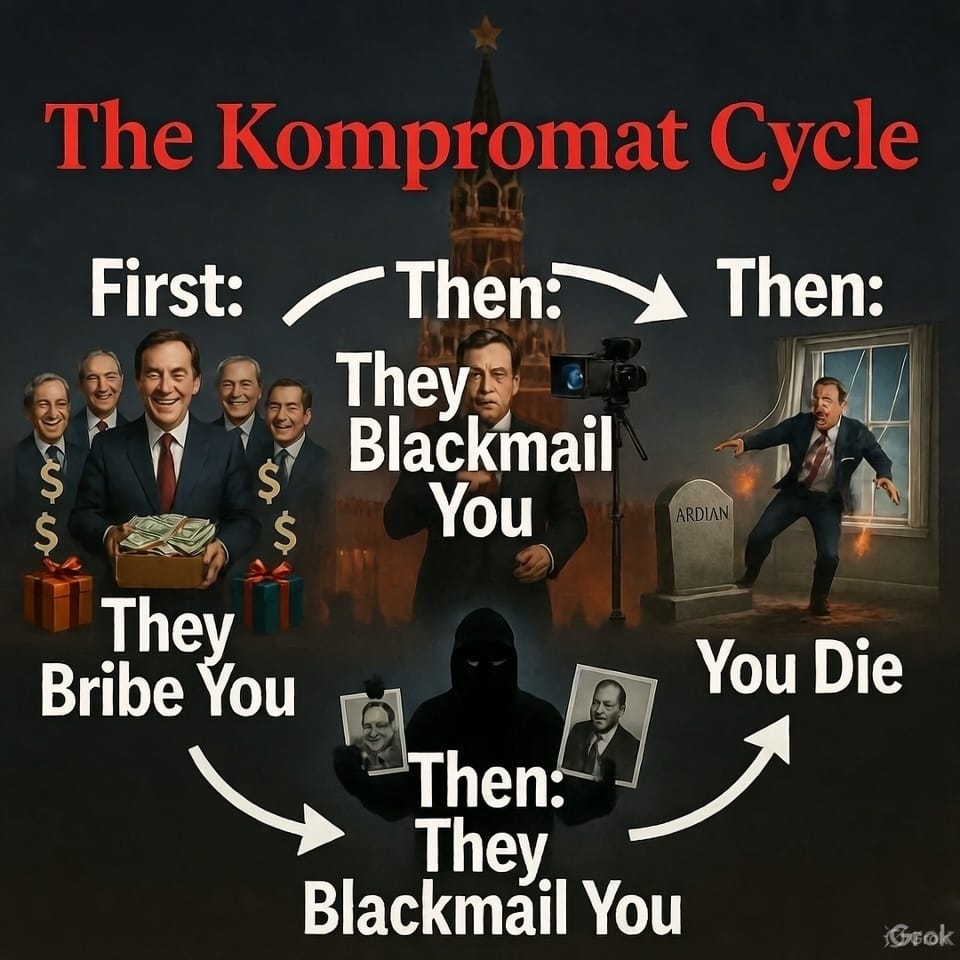

She explained the system’s escalation. First, they try to buy you with money and opportunity. If that doesn’t work, they find leverage to coerce you: scandals, blackmail, compromising situations. Sexual compromise has always been a favored tool. Get someone on camera in a compromising position, create leverage, ensure compliance.

If that doesn’t work, they kill you.

Claudine made the stakes clear: “Once you’re in, you’re in for life.” And talking about the work would make life dangerous.

After their final meeting, Claudine disappeared. When Perkins tried to find her years later, there was no record she’d ever worked at the company.

The Formula in Practice

Perkins arrived in Indonesia in 1971 with a mission: justify World Bank loans for a massive electrical grid. Another economist, Howard Parker, projected honest eight percent growth. Perkins’ bosses wanted different numbers. They told him to project 17 to 20 percent annual growth.

Parker called it a scam and refused to participate. He was fired for his “ridiculous low forecasts.” Perkins was promoted, doctored Parker’s report, and the inflated projections stood. The loans were approved. American companies got the contracts. Indonesia got the debt.

One evening, Perkins attended a traditional puppet show. The puppet master performed a piece where puppets depicted President Nixon and an American henchman eating up small countries, spitting them into a bucket. As they destroyed Indonesia, another puppet representing a local politician tried to stop them and was dramatically slain on stage.

Days later, that real politician was killed in a hit-and-run. The prophecy had been a warning.

Omar Torrijos was different from other leaders Perkins encountered. The Panamanian general actually cared about his people. When Perkins arrived in Panama in 1972, Torrijos called him in for a private meeting and made an unusual offer: tell me the truth about what these loans will do to Panama, and I’ll make sure you’re paid well for your honesty.

It was a test. Torrijos was offering Perkins a way out of the system.

Perkins provided honest analysis. Torrijos used it to make better decisions. In 1977, Torrijos signed the Canal Treaty with President Carter. After decades of American control, the canal would revert to Panama in 1999.

Then Torrijos made a move that sealed his fate. He began negotiating with the Japanese to build a new sea-level canal, financed entirely by Japan. This threatened American interests and the revolving door between construction conglomerates and the Reagan administration cabinet.

Three thousand miles away, President Jaime Roldós of Ecuador was making similar trouble. He opposed Operation Condor, the CIA program supporting right-wing dictatorships. He wanted Ecuador’s oil wealth to benefit Ecuadorians, not foreign corporations.

Both leaders rejected the bribes. Both resisted the coercion. In the language Claudine had taught Perkins, the economic hit men had failed. And when economic hit men fail, the jackals come.

On May 24, 1981, Jaime Roldós died in a plane crash. He was 40.

Torrijos told his family: “If the CIA killed my friend Jaime, I’ll probably be next.”

Ninety-seven days later, Omar Torrijos died in a plane crash. He was 52.

Twenty Years of Silence

Perkins started writing in 1982. He called it “Conscience of an Economic Hit Man” and planned to dedicate it to Roldós and Torrijos.

But every time he tried, something stopped him. Legal threats. Bribes. Reminders of what happened to people who talked. In the early 1980s, he accepted what he calls a bribe: a lucrative consulting position that paid him not to write.

Twenty years passed. Perkins became wealthy, lectured at Harvard, consulted for major corporations. He lived well on the profits of the system. But the deaths never left him. And Claudine’s warning kept him quiet.

September 11 and the Breaking Point

Perkins watched the towers fall and saw blowback. The rage driving those attacks had roots, he believed, in exactly the policies he’d helped implement across the Middle East and beyond. The economic warfare. The exploitation. The backing of dictators. The decades of humiliation.

His daughter had graduated college and entered the world she would inherit. That thought became unbearable.

In 2004, Perkins published “Confessions of an Economic Hit Man.”

He named the system: corporatocracy. A network of corporations, banks, and governments working together to expand American empire through debt instead of armies. He detailed the methods: fraudulent forecasts, massive loans, guaranteed contracts, unpayable debt that gave America control over resources, policies, UN votes, and military bases.

He explained the escalation: when economic hit men fail to corrupt a leader, the jackals move in. CIA-sponsored operatives arrange coups or assassinations. And when the jackals fail, the military invades. Panama in 1989. Iraq in 1991 and 2003.

He dedicated the book to Jaime Roldós and Omar Torrijos, the two men who wouldn’t be bought.

The Establishment Strikes Back

The Washington Post called Perkins “a frothing conspiracy theorist, a vainglorious peddler of nonsense.” The State Department said there was no evidence the NSA had been involved in his hiring. Boston Magazine called his documentation “flimsy.”

Even Einar Greve, the man who’d hired him, initially told journalists: “Basically his story is true. What John’s book says is, there was a conspiracy to put all these countries on the hook, and that happened. Many of these countries are still over the barrel and have never been able to repay the loans.”

But then Greve changed his tune. He denied the NSA connection, said Claudine Martin never seduced Perkins, and suggested Perkins had “convinced himself that a lot of this stuff is true.”

The book became a bestseller anyway.

Veterans who’d served in the Panama Canal Zone wrote reviews saying they’d seen exactly what Perkins described. People whose parents had worked for multinational corporations said the stories matched what they’d heard at dinner tables. Critics in Latin America, Africa, and Asia said Perkins was finally telling their history from the inside.

The book spent over 70 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and sold millions of copies in more than 30 languages.

The Pattern of Control

The escalation Perkins described resembles what intelligence agencies call kompromat operations: first offering money and access, then using compromise and blackmail when bribes fail, finally arranging “accidents” when coercion fails. The Jeffrey Epstein operation allegedly followed this model. First offering access and money to powerful people, then using hidden cameras and compromising situations to create leverage. Alleged intelligence connections. International operation. Targeting influential people. When Epstein himself became a liability, he died in a jail cell under circumstances that raised more questions than they answered.

Different contexts, same pattern: bribe, compromise, eliminate.

The System Evolves and Expands

In 2016, Perkins published a second edition showing how the economic hit man strategy had come home to America, used against U.S. cities and states through the same debt mechanisms.

In 2023, he released a third edition focused on China. The Chinese had studied the American playbook, perfected it, and deployed it through the Belt and Road Initiative. Same formula: loans flow from state banks to developing countries and straight to contractors from the creditor nation. The country gets the debt. When they can’t pay, the creditor gets control of ports, resources, policy.

Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Zambia, and dozens of others are caught in the trap. Ecuador’s President Rafael Correa had read Perkins’ book and understood the system. He tried to negotiate better terms. By 2018, Ecuador owed China billions with no way to repay.

A 2011 ETH Zurich study found that 147 firms control 40 percent of global wealth. The concentration hasn’t diminished. It’s intensified. Now two empires compete using the same methods, racing to trap more countries faster.

The Pattern Spans Millennia

John Perkins exposed one iteration of a much older system. Carroll Quigley, given privileged access to Council on Foreign Relations archives, documented elite networks from the inside. Antony Sutton used his Hoover Institution position to expose Wall Street financing of totalitarian regimes. Charlotte Iserbyt smuggled documents revealing education transformation. Each insider described a piece of the same machinery.

This is the thesis of “The Hidden Hand: Wealth, Power, and Control from Pharaohs to Corporations” by Eric Daniel Buesing. Drawing on 22 years of research, Buesing traces how elite power structures have evolved from Sumerian temple economies through modern corporate networks.

What Perkins described as economic hit men, what Quigley documented in elite networks, what Sutton exposed in financial backing of totalitarianism, what Iserbyt witnessed in education: Buesing shows these aren’t aberrations. They’re the latest iterations of methods elites have used for millennia.

The tools change. Cuneiform tablets become balance sheets. Temple priests become foundation executives. Tribute becomes debt service. But the structure remains: a small group of oligarchs controlling wealth and power, operating through layers of institutions, using economic leverage to enforce compliance.

The pattern is ancient. When Hammurabi ruled Babylon in 1750 BC, elites already used debt to control populations. Bribe the provincial governor with gold. If he refuses, blackmail him with evidence of scandal. If that fails, arrange a convenient accident. The revolving door between construction conglomerates and government cabinets follows a template established when merchants and monarchs first learned to share power.

“The Hidden Hand” connects the dots across five millennia, showing how the fundamental mechanisms of elite control have survived every revolution, adapted to every economic system, and operated through every form of government humanity has tried.

The book is available for pre-order at Barnes & Noble and will be released on June 22, 2026.

The Questions That Won’t Go Away

The CIA doesn’t release operational details. Claudine Martin never came forward. No paper trail connects the NSA to Perkins’ hiring.

Yet millions found him credible. People who’d witnessed similar systems recognized the patterns.

Whether he was truly an NSA-recruited operative or an economist who witnessed predatory lending and constructed a dramatic narrative, he named a system that continues operating.

How much of American influence operates through economic leverage rather than diplomacy? How often do infrastructure loans deliberately trap nations in debt dependency? When leaders resist, what actually happens to them?

If the system Perkins described doesn’t exist, why do the patterns repeat with such predictable precision?

Two plane crashes in 1981 broke John Perkins’ silence. But the silence about how power actually operates in the global economy persists, protected by complexity, defended by institutions, maintained by those who profit.

The truth, as Perkins discovered, can make life dangerous. But sometimes the cost of silence becomes unbearable.